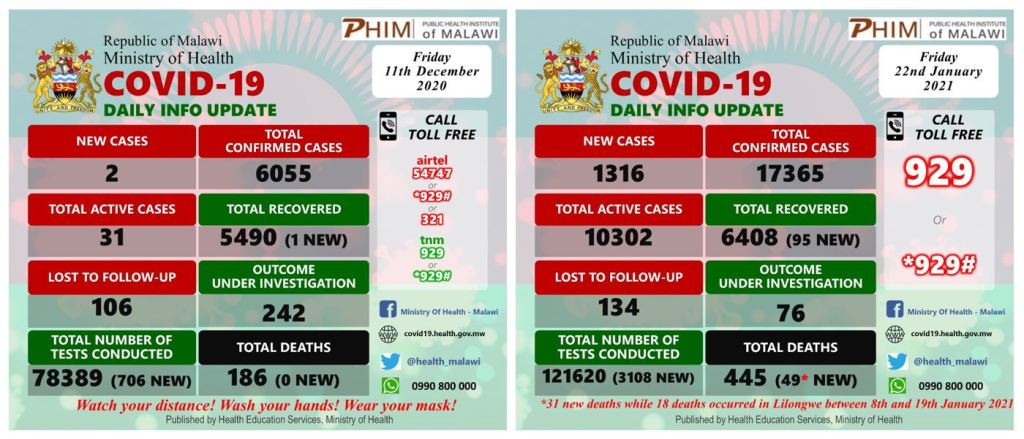

When we headed out to Kenya for our Rest and Relaxation (R&R) trip on December 11, things on the COVID-19 front seemed to be looking up. There was of course a second wave already beginning in Europe, the U.S., and South Africa, but the numbers in Malawi had dwindled to almost new cases. In Kenya, there were rising numbers, too, but I had done some personal calculus and decided that if we needed a vacation outside of Malawi (and when I tell you *I* needed a vacation somewhere other than Malawi after a year, I mean it) then Kenya was the place to go.

Yet in the course of our three-week trip, the numbers started again to rise in Malawi and on December 23, with a week left in Kenya, the Malawian government announced a two-week border closure. The idea was to reduce the number of imported cases, though to be honest, these incidents were not of foreigners entering the country, as Malawi is at the end of line and even in a non-pandemic year captures only 1% of Africa’s 67 million tourists, but rather Malawian deportees from South Africa. No border closure that is not closed to citizens (which naturally it would not be) was not going to stop the cases coming in. But it was already too late.

When we returned on December 30, the country registered 83 new cases. For those in countries like the United States, Brazil, India, Turkey, Mexico, or much of Europe, this may seem an incredibly low number and not something to be concerned about. However, Malawi had not registered that number of single day positive cases since August 7. And keep in mind that Malawi is one of the poorest countries in the world. It has one of the lowest doctors per person ratios in the world. In a 2020 Malawi College of Medicine survey of 255 hospitals, only a quarter reported reliable electricity, about a half had hand soap, and only one-third had oxygen supplies. In June 2020, the entire country had only seventeen ventilators and twenty-five intensive care beds for a population of 18 million (in El Paso, Texas, with a population of less than 700,000, there are 400 intensive care beds). Eighty-three positive cases, had they all been serious, would have overwhelmed Malawi’s intensive care facilities.

Soon after our return, C and I headed out to a supermarket and to get takeaway from a restaurant in downtown Lilongwe. In the supermarket, although there were signs at the entrance regarding masks, the vast majority of customers were not wearing any. The two cashiers I saw had theirs hugging their chins. At the cash register, a man got in line behind us and in doing so, brought his mask down to his chin (rather than put it up). At the food court, where several fast food joints serving chicken, ice cream, and pizza, and which was doing a roaring business, only one person other than us had on their mask. The servers, cashiers, patrons and management had no protective equipment at all. When I asked the manager why not, he told me that there were no reasons to do so, no regulations. I knew that to be false as the Lilongwe city government had put a mask policy in place back in July or August, and which included a potential 10,000 Malawi Kwacha ($13) fine for non-compliance. I suspected it was more a matter of little to no enforcement. After having spent the previous three weeks in Kenya where the government was very serious about COVID-19 mitigation measures, this came as a bit of a shock.

Despite the closed borders, there were reports of big gatherings for the holidays. The January 1 newspapers covered the New Year’s Eve events including parties and concerts, one including a South African musician.

Over the next several weeks, we watched as the numbers of positive cases climbed rapidly. Between December 11, which reflected over eight months of the pandemic in Malawi, and January 17, the total confirmed cases doubled. During this time frame, two Cabinet ministers and two other senior government officials died from COVID. The President announced on January 17 the government would impose a curfew (between 9 PM and 5 AM), enforce mask wearing, enforce early closure of markets (5 PM) and drinking establishments (8 PM), and close schools. By January 22, which would turn out to be the reported height of the second wave, the numbers were nearly threefold the eight month total. Between then and February 1, the number would be fourfold. Two more Members of Parliament, two local councilors (district level elected officials), a music icon, and 252 other Malawians died. The numbers then began to decrease. Field hospitals were set up, resources were put into the government response, the international community donated equipment. Parliament postponed the opening of its Mid-Year Budget Review Session as rumors of some 10-40+ of its 193 members were reportedly COVID positive. It took until February 19 to see the five fold increase. Another member of parliament and 291 others in Malawi died. As of February 28, Malawi had surpassed a sixfold increase of its first eight months of COVID, in a three month timeframe.

Though we all breath a bit of a sigh of relief to see those higher numbers of January gone, the current daily numbers still hover around the high marks of the first wave. Although the government reopened schools on February 22, teachers, demanding protective equipment and hazard pay, refused to work. Three days after beginning the postponed parliamentary session, the Speaker of Parliament tested positive for COVID. Yet still, with the first order of vaccines for Malawi expected to arrive soon and the vaccination roll-out to begin some time this month, there is a sense of hope that this is the beginning of the end of the pandemic.

Though we have been living this pandemic for a year now, and we have certainly (largely begrudgingly) adjusted, C and I too are hoping for an end to the pandemic, to a resumption of some sense of normalcy, sooner rather than later (like everyone else on the planet). We have through this year been incredibly lucky compared to so many, and I am grateful we have been able to ride out this challenging time in Malawi, a beautiful country we call home. But we are so ready to have our last months in Malawi be ones without the cloud of the pandemic hanging over us.