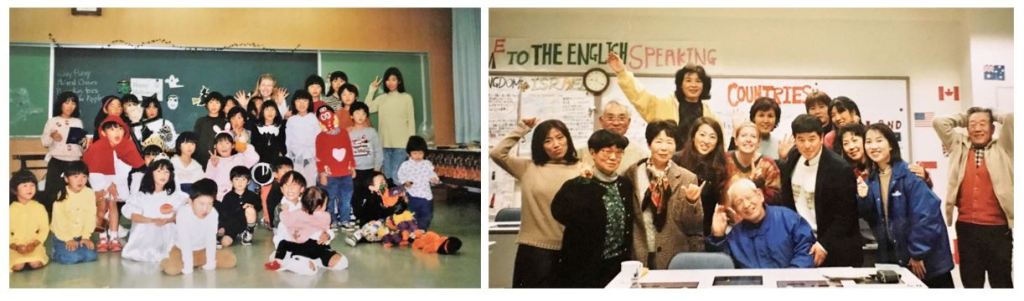

In July 1997 I arrived in the small coastal town of Kogushi (which translates as “little stick”) to teach English as part of the Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) Program. This is the fifth and final in a series of posts about my three years in Kogushi.

When I was in Japan on the JET Program – and it could very much be the same now, I do not know – the vacation days were set by the prefecture. The vast majority of prefectures gave the JET teachers 15 days of vacation, though some lucky JETs got 20 days, and the sad folks in Tottori Prefecture got only 10. Yamaguchi Prefecture, where Kogushi was located and where I taught, gave 15. The thing was, there were far more than 15 days with the school closed. The school year was divided into trimesters with the first beginning the second week of April and ending around July 20, the second starting around September 1 and ending around December 20, and the third beginning around the second week of January and ending the third week of March.

Basically school was closed for 12 weeks of the year. The students were at home; the teachers, who often had been transferred from far away, headed to their home prefectures. I came to love the small fishing village of Kogushi in many ways, but I just could not sit there alone in that apartment, that town, for all but 15 days a year. Part of loving it was being able to leave and then return. The prefecture had another policy — if you traveled within Japan, you did not need to use your 15 days. You didn’t need to tell me twice.

I did travel outside of Japan – a trip to New Zealand, also to Australia, one to Bangladesh, another to Thailand, a two week trip to Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium, and a week in Taiwan. But I also made the most of living in such a fascinating country. I traveled all across the country – to three of the four main islands (Honshu, Kyushu, and Shikoku), and to at least 22 of the 47 prefectures. I went by slow local train and fast (the shinkansen or bullet train). I took overnight ferries (from Kitakyushu to Takushima, Ehime to Osaka, Kitakyushu direct to Osaka, and from Kobe to Kitakyushu). I also twice took long distance buses — but after a bus breakdown followed by being left behind at a rest stop at midnight on the way back from Tokyo (I ran after the bus through the parking lot and luckily one person remembered the foreigner on the bus and the driver stopped – this was memorable!) and having the bus on which I was traveling on a return trip from Tottori getting hit by a truck…I did not find Japanese bus travel as reliable. Sadly, my memories are so faded, but there are some that still stand out.

Okinawa. I wish I remembered more about my trip here. I do not remember how many days I visited or where all I went; I do not even remember visiting Shuri Castle though I have photographic proof that I at least stood in front of it. What I do remember are two incidents. In the first, I took a bus north of the capital of Naha to visit the 18th century historical Nakamura residence. The bus I ended up on was the wrong one or it was not going all the way to the house that day because of the day or the time. By car the trip would take 25 minutes, but by bus over an hour. And when after an hour I realized the bus was not going to the right spot, I was pretty bummed. But I was the only one on the bus and the kindly bus driver decided to take me straight to the site, completely off his route. A backpacker’s hero! In the second instance, I just went to the mall to buy clothes. I figured that with the U.S. military base, there might be more sizes that fit me. Though I was a size small in the US, I felt like Gigantor in Japan. But sadly, I tried on a pair of jeans in size “large” and could not get them over my thighs and found myself stuck in a “one size fits all” shirt. I thought I would have to ask a Japanese sales clerk to come to the dressing room to help me out though I knew that would probably be worse as the women often ran away giggling when I tried to ask questions (a perennial problem in Korea and Japan, at least at that time).

Tokyo and its environs. Between my first and second years in Japan, I signed up to take part in a two week Japanese course through the Tokyo YMCA. The YMCA set up a homestay for me with a family in Yokohama. I remember almost nothing from the Japanese course itself — I don’t think it did much for my Japanese — it was more the being in Tokyo, about as far away in Japan from Kogushi as I could get: the opposite side of the country and a megapolis compared to a village. What sticks out the most from that trip was my homestay family — a two parent family, with dedicated working dad, a stay at home mom, two elementary aged kids. What made them so memorable was their keen dedication to Disney. The had annual passes to Tokyo Disneyland, had Disney decor around their home, and they named their two girls after Disney characters. I also remember meeting up with Miyako, a young mother who had befriended me in Kogushi when I entered a local government building seeking information on town recycling. No one could help me, but her husband called her — with her excellent English — to assist. We started to hang out and I even briefly joined her husband’s band. I sang the Beatles songs at a wedding. Miyako was back in Tokyo with her son and we went for a cruise on the Sumida river. Then I visited Senso Temple, Tokyo’s oldest. It is a magnificent temple of bright, colorful red buildings, including a pagoda, and is one of the city’s most significant — though anyone can tell this from reading online. I do not actually remember. What I do recall is demonstrating a high level of patience waiting by the massive red paper lantern at the “Thunder Gate” until there were few people so I could jump in and get a silly photo of me below it.

Osaka to Yamaguchi. One year for Golden Week, a period at the end of April and early May when multiple Japanese holidays (Showa Day to honor the WWII Japanese Emperor on April 29, Constitution Day on May 3, Green Day on May 4, and Children’s/Boy’s Day on May 5) coincide, I decided to take an overnight ferry to Osaka and then work my way back to Yamaguchi. While in Japan I took several overnight ferries — and even twice to/from Korea — and they were rather fun — much less expensive than the bullet train and it saved a night of accommodation. These boats were huge with large sleeping rooms for maybe 50 people complete with roll out tatami mats with blankets (at least in the 2nd class dormitory) and a massive dining room. There was a gentle rocking throughout the journey, though I fared better on these big boats than I have on smaller vessels. I docked in Osaka and spent a night or two there (I had a few trips to Osaka — once for a JET Program second year conference, another time to meet up with my friend CZ who came to visit me in Japan, and then this trip — so they blur together a bit). I recall visiting Nara and feeding the wild deer and running into a Japanese celebrity. Well, its a bit embarrassing, but the “celebrity” was a young, blonde American girl of about 12 who starred in a Japanese kids show. I watched the show regularly because they mixed in English and so I could follow the plot… From Osaka, I took the train west to the town of Himeji in Hyogo province to visit the incomparable Himeji Castle, considered Japan’s best. I wish I remember the castle itself; I don’t even have any photos of the interior, but what I remember is walking the grounds, crossing the moat, and catching a beautiful view of the castle and the streamers of carp flags strewn in celebration of Children’s Day. I headed next to Okayama city, Okayama Prefecture. I had almost forgotten about this stop completely til as I was writing this I had a sudden recollection of biking through some fields and of a very strict hostel. My roommate from my Korea days had been a JET in Okayama and had recommended the Kibi Plain cycling route, which wound past historic sites and rice paddies. My next stop was Hiroshima and then the iconic Itsukushima “floating” shrine before heading home.

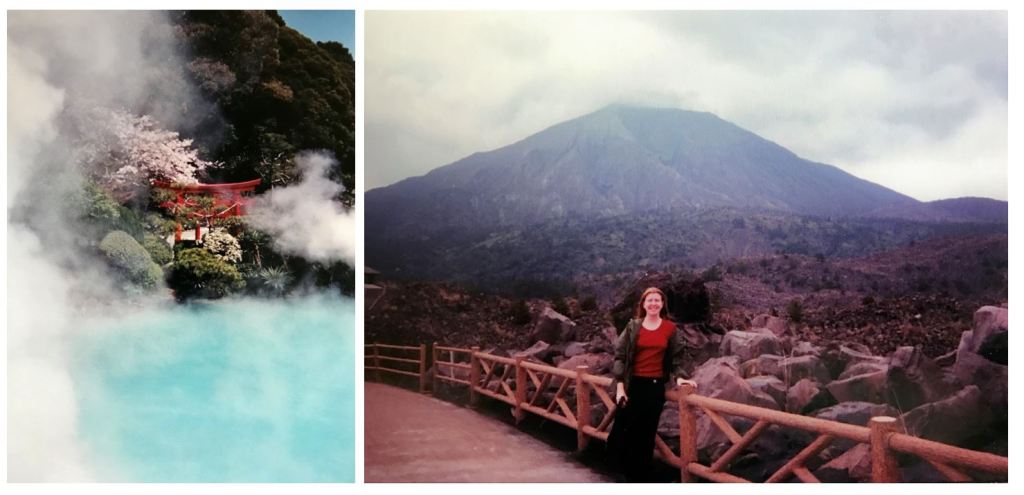

The Kyushu Hot Springs Tour. While in Japan, I came to really love the hot springs or onsen. I had been introduced to the concept while teaching English in Seoul, South Korea, where I lived on the top floor of a four story walk-up. The building, painted a deep purple, and over a shoe store, had terrible plumbing, and the large, cheerless, bathroom, I shared with two roommates was not really up to task. But down the street, just a few blocks away, was a traditional public bathhouse. It was here where I 3-4 times a week (in conjunction with the shower at my gym) came to suds up alongside other neighborhood women. I was quite thrilled when I moved to Kogushi and learned that just one town over was the famous Kawata Onsen. But I was not satisfied to just head over there to fulfill my onsen interests, I started to motorbike around the district and prefecture to other hot springs and to seek them out in other locations. There were indoor onsens and outdoor onsens. Modern onsens and traditional onsens. Obscure onsens and famous onsens. And onsens that offered unique experiences such as varying temperatures, an electric bath (this was quite literally shocking and made me really uncomfortable), and more. I never did get up to Hokkaido or northern Honshu (known as “snow country”) for an au naturel soak surrounded by snow and mischievous monkeys, but I did visit the famous Tamatsukuri Onsen in Shimane prefecture and the Dogo Onsen Honkan in Ehime Prefecture, reportedly Japan’s oldest hot springs resort. Thus, in my third year in Japan, I made it my mission to visit some of Kyushu’s most famous.

I traveled first with my friend Hiroko to Saga Prefecture, where we bathed to our hearts content at the 1000+ year old Takeo Onsen. We then traveled together to Nagasaki to visit the Peace Park commemorating the atomic bombing of the city that ended WWII. Hiroko headed back home while I continued on to Kurokawa Onsen in Kumamoto Prefecture, among the country’s top ten. Further south I visited Kagoshima and Sakurajima for their onsen and I finished up at the famous springs of Beppu in Oita Prefecture. Of this whole trip, my biggest memories are of Kagoshima. Here, I partook of the famous “sand bath,” where women bury you in hot sand warmed by the very active Sakurajima volcano. It seemed innocent enough — undressing and then wrapping oneself in a specially provided robe, following two women with buckets and pails out to the beach, and then have them dig a hole in the sand to get into. And this though is when it got weird. I realized I never liked being buried in sand at the seaside. Heavy enough when it is perfectly dry, when its damp and steaming hot, it was suffocating. Ten minutes in that inferno is supposed to be enough to sweat out all one’s impurities, and I was counting down the seconds. My other big memory was of staying on Sakurajima – literally Cherry Blossom island – which was turned into a peninsula after a 1914 volcanic eruption. I stayed two uncomfortable nights. The hostel was comfy enough, it was the proximity to the smoking mountain that made me leery. But it was after enjoying a soak at the Sakurajima Maguma (I am pretty sure this is Japanese for “magma”) Onsen, with its beautiful view of the ocean from its outdoor bath, that I hitchhiked for the very first time.

Not that I have made it a habit — I’ve done it I think five times in my life? But when I came out of the onsen and realized it would be awhile before a bus came — if at all — and the walk back to the hostel would take an hour at least, the Japanese teenager that stopped to give me a lift was like a godsend. I remember a tape deck, some music we both liked, and the both of us trying to muddle our way through a conversation in broken English and broken Japanese.

Shimonoseki. Travel did not even have to be particularly far afield. There were onsens and the Mara Kannon fertility temple (with its hundreds of large and small stone phalluses) and the five story pagoda in Yamaguchi City to be found in my own prefecture. My favorite place though was the Akama Shrine in Shimonoseki. Dedicated to the child emperor Antoku who was drowned by his grandmother during a major sea battle in the Shimonoseki Strait between warring clans in the year 1185. When in Shimonoseki, I would often stop by here, it commands a beautiful view over the strait and towards the Kanmon bridge linking the islands of Honshu and Kyushu. I took my mom and aunt here when they visited, I went with friends, I glimpsed a wedding there once. But the best time was when I attended the Shimonoseki Kaikyo Festival. I had missed this festival my first two years as it fell during Golden Week, a time I was normally away, but I was low on vacation time and money, so I stayed in Kogushi. I was pretty intent on being miserable stuck in my little town, but friends invited me to attend the festival with them. It recreates the naval battle and the capitulation of the Heike clan to the Minamoto. But the most anticipated part is the walk of the Heike women to the shrine. A bridge is erected for the women, dressed as geisha, and representing different ranks. The higher the rank, the higher the geta or traditional Japanese wooden shoe and the more exaggerated their walk. The finale is when the highest of the women representing the fallen Heike women, dressed in the most gorgeous and elaborate kimono, with her multi inch high geta, slowly, and deliberately walks toward the shrine, the sides of the geta dragging along the path as she makes wide arcs with her feet, puffing out her heavy robes. It is sober and beautiful.

It is interesting to delve deep into my memories to see what survived the decades. I am a huge fan of travel and have been all over the world and yet despite my love of visiting new countries and cultures, there is only so much that I have retained. My three years in the town of Kogushi, Little Stick, have no doubt shaped my life in myriad ways. Just as I am sure my four years in Malawi will forever be a large part of who myself and my daughter are going forward.