With current events being what they are, I thought this would be a good time to get into my way back machine and revisit a trip I took a long time ago. To go back to before I worked for the federal government, back before I was a mom, and before I grew old and my parents older. From July 2002 to July 2003, I lived in Singapore while pursuing a Master’s in Southeast Asian Studies. As Kismet would have it, a few months into my degree I discovered my high school friend CC was also in the country working at an advertising agency. CC and I decided to take a weekend and head up the Malaysian peninsula to Melaka together.

Melaka is but a quick, comfortable four-hour bus ride from central Singapore. I met CC early on a Saturday for the journey. All I remember is the bus was nice and CC and I talked the whole time. I know it must have been an easy trip as I do not recall anything special about it. I have been on very many types of transport around the world, and though it’s nice to have a straightforward trip, it’s the uncomfortable and weird journeys that make the best stories.

Melaka (spelled “Malacca” by the British) is quite possibly Malaysia’s most famous city outside of the capital. Owing to its strategic location halfway along the Strait of Malacca, a long-vital maritime route, and at the mouth of the Melaka River, Melaka has served as a crossroads, port, and home for many cultures over the centuries. In the 1400s it was the seat of a sultanate, from 1511-1641 a possession of the Portuguese, from 1641 to 1824 a Dutch holding, then ceded to the British until Malaysia’s independence in 1957. Chinese envoys and tradespeople made Melaka a key commercial stop and immigration destination. As I wrote in 2003: It is a fascinating little city with architectural representations of each of its colonial rulers and the Malay, Chinese, and Muslim influences of its past and present. It seems like a place out of time, an almost European city plunked down in tropical Southeast Asia, with a Muslim Malay population with a heavily Chinese influence.

We stayed at the Eastern Heritage Guesthouse, an inexpensive lodging house in a traditional southern Chinese shophouse on Jalan Bukit Cina (China Hill Street) near the city center. Percentage Boy was the front desk clerk and jack of all trades at the Eastern Heritage Guesthouse. When we stopped in to inquire about a vacancy, we asked to see the room first. We thought it was nice, but CC wanted a room with an attached bath, and the Eastern Heritage Guesthouse didn’t have any. We asked Percentage Boy if he knew of other places with similar prices and attached baths nearby. He assured us there were some, but mentioned that approximately 75% of visitors to his guesthouse decided to stay. After some discussion, we, too, came around to Percentage Boy’s persuasive nature. It was after all only 22 ringgit a night, which came out to 11 ringgit each or six and a half Singapore dollars each or four U.S. dollars each. We were sold.

Downstairs, as we entered our details in the guesthouse registry, I asked Percentage Boy if he spoke Malay, hoping to practice mine. He mentioned that he knew about 80% of Malay. I then asked about his Chinese. He responded that he spoke approximately 10% Chinese, about 90% English, 5% German, and 5% Italian. I tried not to roll my eyes. As CC and I exited, he provided us with a map and suggested we might be interested in the Laser Light show, as nearly 95% of his guests had reported enjoying it. However, the lady at the tourist information center informed us that the show was not running at the moment, although we discovered the next day that it had been. I wondered what percentage of visitors received the wrong information from Tourist Info Lady.

The Eastern Heritage Guesthouse, now permanently closed, sat about midway down a street of faded Chinese shophouses built in a style typical of the Straits Chinese. Downstairs the front of the building facing the street housed the family’s shop, while in the back and upstairs the family home. While living in Singapore, I visited the National Museum of Singapore during an exhibition on the Straits Chinese and was keen to see more of the culture.

Also known as Peranakan or Baba Nonya culture, the early southern Chinese who arrived on the Malay peninsula between the 14th and 17th centuries developed a unique amalgamation of Malay, Dutch, and Chinese culture. Their beautiful shophouses line many of the streets in Melaka; several have been turned into graceful hotels, interesting boutiques, and atmospheric restaurants.

CC and I walked towards the historic center of Melaka to take in what is known as Red Dutch Square, an area characterized by 17th- and 18th-century Dutch buildings, including the Stadthuys or “city hall” (considered the oldest Dutch building in Asia) and the Dutch Anglican Christ Church (the oldest Protestant Church in Malaysia), and supplemented later by the British, who built the free school and the Queen Victoria fountain, and the Chinese, who built the clocktower. We next visited the ruins of the Portuguese Church of St. Paul, built between 1566 and 1590.

We poked about in shops, had a fantastic foot reflexology session, and gobbled up delicious wood-fired pizza in a refurbished shophouse. We also strolled through the Jonker Street Night Market, which was certainly lively, but lacked the jostling crowds we had experienced in Singapore.

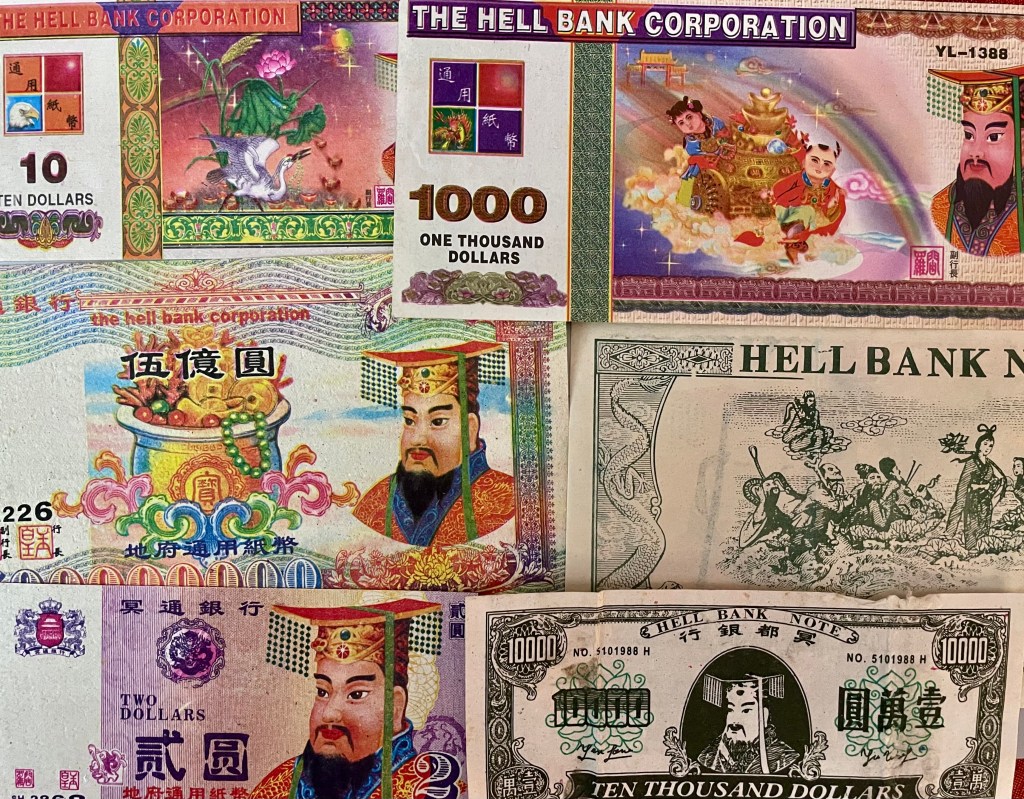

While window shopping, I found a large stock of “hell money,” incense paper resembling various currencies, used in Chinese ancestral worship. By burning the currencies, people transfer funds from the living world to their deceased family members in the spirit world to ensure they will have sufficient funds in the afterlife to buy necessities and luxuries, pay bribes, or atone for their sins. Most hell money notes are high denominations. As a long-time currency collector, I had to buy some to add some to my collection.

On our second and last day, Percentage Boy had one more opportunity to impress us with his statistical knowledge: At breakfast the next morning, Percentage Boy asked if we wanted toast with jam or eggs. We both ordered the egg, which seemed to confuse the boy as he noted that 75% of female guests ordered the toast and 90% of male guests ordered the eggs. We explained that we were hungry women. He seemed dubious.

Before we left Melaka we took a riverboat tour and met the talkative tour guide, whom I dubbed Loquacious Captain. We should have guessed something was up when his disembodied yet friendly voice welcomed us on board through the intercom with “Welcome. Welkommen. Selamat Datang. Huanying.” This guy was full of character. He gave tons of information about the town of Melaka, the sights along the river, and just about everything else. Every monitor lizard we saw along the river had a name: Antonio Banderas, Sean Connery, Michael Douglas, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Charlie. He spent much of the return journey saying goodbye to us…in as many languages as possible: “I would like to thank you on behalf of the tourist office of Melaka, myself, the boat captain, the crew, the Ministry of Tourism of Malaysia, the Prime Minister, and all the people of Malaysia– Thank You, Terima Kasih, Xie Xie, Arigato, Gracias, Merci, Danke Shon, Selamat Po, and for my friends from Russia Spaciba, to the Koreans Kamsahamnida, Shukriya to our Hindi friends, we want to thank all of you and to say Goodbye, So long, Farewell, Adios, Arrivederci, Ciao, Zaijian, Selamat jalan, Salaam, Adieu, G’day mates to those from Australia, Cheerios to our friends from Britain, Au revoir, Auf Wiedersehen, Aloha to the Hawaiians, Namaste, Sayonara, Do Svidanja to our Russian friends, thank you and goodbye, and as they say in Texas, you all come back now ya hear.”

I wish I had written more about and taken more photos of our trip to Melaka. It was a long time ago and a quick trip. Someday, I would love to return with my daughter. Five years after my visit Melaka, along with the Malaysian city of George Town, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its extraordinary blend of cultures and architectural styles. I hope the designation has led to funding and visitor interest in protecting this beautiful town. Though the faded, peeling paint jobs, broken shutters, and crumbling facades provided a certain atmosphere, future generations deserve to enjoy them too.