For me, one of the great things about travel is getting a glimpse, even a mini immersion into the history, politics, and culture of another country. I especially like seeing the quirky (or what seems quirky to me) aspects in a place. Japan, in particular, seems to celebrate its whimsical and weird side and these parts of Japanese culture are well-known and popularized even outside of the country. For example, the plethora of vending machines or the counter-culture fashion of the Harajuku girls. I wanted to highlight a few of these aspects of Japan that came up during our trip: Hello Kitty, Pokémon, and signage.

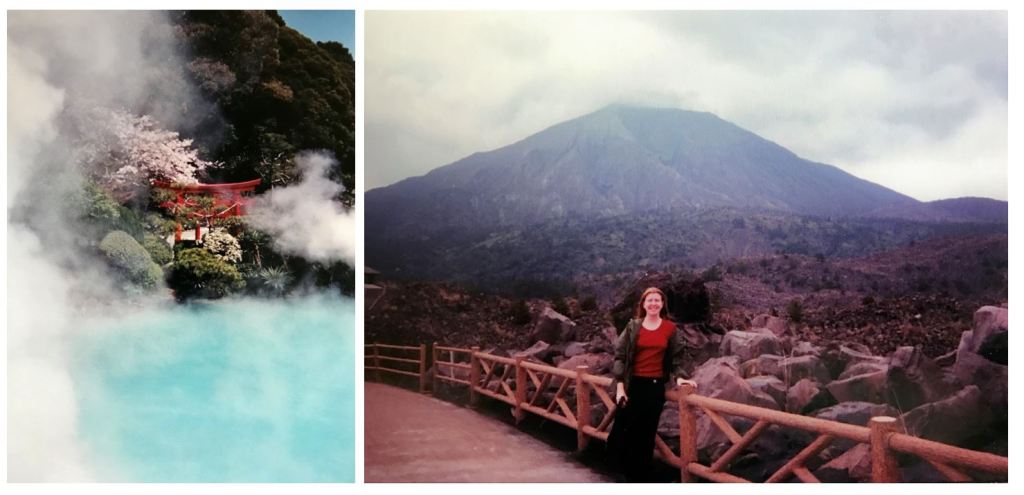

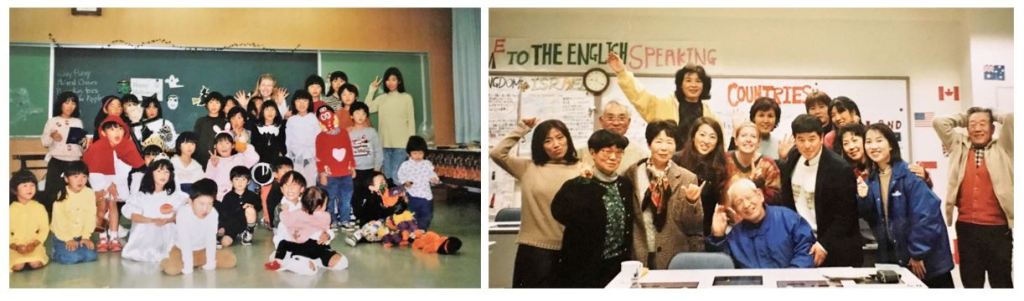

I am a Gen-Xer and I have a collection of Hello Kitty items. There, I said it. I did not start out as a Hello Kitty fan. What happened was this: When I went to Japan in the late 1990s to teach English, a former college roommate of mine told me how when she was a little girl she had a Hello Kitty purse that she loved. So, to make things a little fun for my friend, I started to send her Hello Kitty-themed care packages. For instance, I sent her a box full of items for the kitchen with Hello Kitty-shaped pasta, chopsticks and cutlery with Hello Kitty’s face, salt and pepper shakers. Then a box of items for the car: a big pink Hello Kitty foldable sunshade, a Hello Kitty air freshener for the review mirror, Hello Kitty ornamentation to stick on her car windows. I also sent a package full of Hello Kitty cosmetics. I had great fun curating the items for the bespoke Hello Kitty gift boxes. My Japanese friends saw me buying these Hello Kitty items and assumed they were for me, and they began to gift me with Hello Kitty items– a Hello Kitty yukata pajama set, Hello Kitty scarf and mittens set–and I began to covet Hello Kitty stuff and bought things for myself. My collection was born.

In Tokyo this past visit, we saw many Hello Kitty and other characters from the Sanrio family-branded items. There was so much Sanrio merch. You can slap the likeness of Hello Kitty or one of her friends, like Kuromi, Cinnamoroll, or My Melody onto an item and it will sell like hotcakes. Of course, character-branded merchandise is nothing new! Disney characters sell in pretty much the same way but you will also find Paw Patrol, Peppa Pig, Harry Potter, or Star Wars merchandise, to name a few. But there seems something so “extra” about Hello Kitty and friends in Japan as the characters are used to sell far more than clothing and accessories.

Sanrio is experiencing a resurgence in the U.S. and exclusive Sanrio clothing collections are being sold in many stores like Forever 21, Hot Topic, or Uniqlo. Some of it is probably related to the 50th anniversary of Hello Kitty this year, though I have seen the goods in greater numbers for the past few years. My 12-year old daughter is a huge fan. She planned to spend some of her hard-earned birthday, Christmas, and allowance money on some Sanrio goods. Her favorite character is Hangyodon, a male fish character, that has been around for years but is not popular in the U.S. She made sure to get some.

Overall, though, my friend CZ and I were a bit disappointed by the Hello Kitty goods we found in Japan this time; these are not the Sanrio stores of the ’90s. Back then, one really could find it all. The stores were bigger; there was far more than plushies, clothing, accessories, and cosmetics. I used to have an edition of a quarterly magazine I picked up sometime around 1998 that featured Hello Kitty goods such as a white wedding dress with the eponymous cat’s face stitched into the lace. There were Hello Kitty TVs (pink, with a cover that pulled down with Hello Kitty on it), toasters, vacuum cleaners, mopeds, cars, and so on. I didn’t see any Hello Kitty shaped pasta or milk sold with a Hello Kitty design. Maybe some of Sanrio’s shine has faded?

Maybe it is because Pokémon has muscled in on the Hello Kitty and friends action? Hello Kitty burst onto the scene back in 1974, but Pokémon were created in 1996. Pokémon is now the highest grossing characters of all time, pulling in even more than the famous Disney mouse. I am too old to have been caught up in the Pokémon craze as a kid, but my daughter is and she caught the bug badly. She plays Pokemon Go, has several of the Nintendo Switch games, and has many plushies, figurines, and how-to drawing books among other things. As a fashion-forward tween, she is a big fan of Sanrio, but Pokémon was her first love.

Though we found less Pokémon goodies than Sanrio, they were still there, and in some unlikely places. Sanrio is most certainly more popular among girls and women and Pokémon’s fan base is about 45% women, there is still a good enough demand for Pokémon-branded cosmetics. I also found there to be more Pokemon-branded food items such as packaged noodles, boxed curry, and sweet and savory snack foods like candy or chips than Sanrio. And I did not find a single Sanrio vending machine, but in our two weeks in Tokyo we did come across two dispensing Pokémon cards and toys.

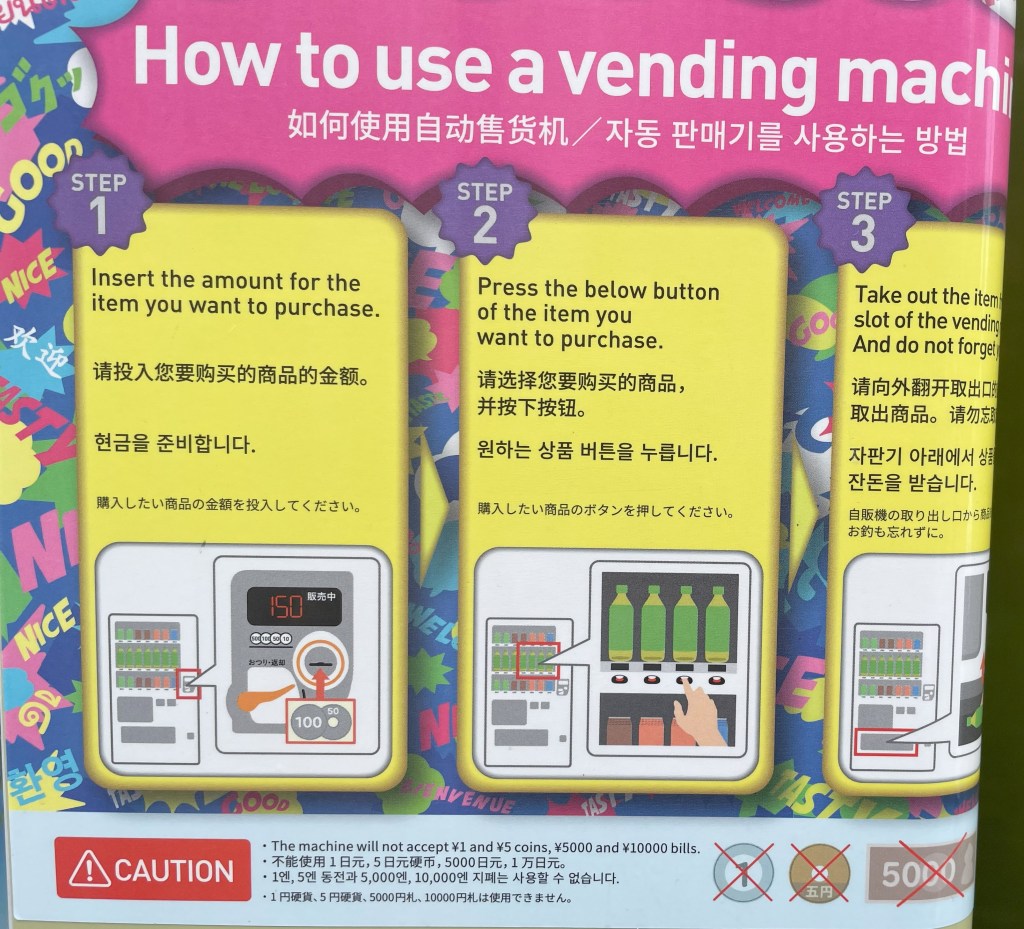

Another thing I found very interesting about Tokyo was the sheer number of signage – to tell folks how to do all manner of things. See, I have a thing about street signs, advertisements, graffiti, murals, and billboards; basically public messaging. I find they can say a lot about a country and/or culture. I wrote a whole blog post about the signage in Malawi, but I also feature signs among my posts in other countries: Singapore, Kenya, Guinea, and Lisbon.

As the Japanese appear to be far more welcoming of animated characters selling items to all ages than say the U.S., it makes sense that signage also often includes cute characters even when explaining less than cute things, even to adults.

What was especially interesting to me is that Japan is considered a high context culture. The level of contextuality of a culture indicates its type of communication. In high context cultures, communication, both verbal and written is more implicit, i.e. that more nonverbal cues/indirect verbal expressions and cultural understandings are used to convey messages, often leaving much unsaid. Japan is considered a very high context culture. While low context cultures, like the U.S., prioritize direct and explicit communication; Americans prefer rules are are literally spelled out. Why then does Tokyo have SO many signs?

I do not know the answer, but I found that signs in Japan often went overboard requesting persons do or do not do things that seem rather self explanatory. Someone I spoke about this with thought the proliferation of signage might be aimed at the city’s expat community or tourists. Maybe. Foreign residents make up less than 5% of the city population, though foreign tourist numbers have been on the rise with over 19 million in 2023. Yet many signs, even those almost entirely in Japanese still include some English verbiage. I expect that just like in the U.S., the inclusion of a foreign language in advertisement can give the messaging a certain coolness factor, and after many years living and working in the region, I find it even more so the case in East Asia.

The most amusing to me though were when I found very long explanations on how to do something fairly commonplace. Why would there need to be a detailed multiple-step explanation on how to operate a vending machine in a country where there is quite literally one on every corner? The same I suppose could be said for how to use a toilet. That would seem to be something folks would learn really early on in their lives, and those who are too young to know, would also be too young to read the detailed how-to. Granted, I have seen such toilet instructions in other parts of Asia, but few as wordy as those I saw in Japan.

For someone who is from such a low-context culture, even I found the Japanese signage to go a bit overboard, but I just chalked it up to one more interesting aspect.

There you have it. Our Tokyo trip in six easy installments. Twenty-odd years since I last visited, and the place still felt familiar. There were still the salarymen in their black suits, white shirts, and briefcases, there just seemed to me more women among them. There were still the Harajuku girls, though perhaps with less fake tan and more understated make-up. There were still the well-stocked convenience stores full of the snacks I fondly recalled from the late 90s: the rice crackers, the vitamin jelly drinks, the onigiri, though the workers behind the till might be from Bangladesh, Nepal, or Kazakhstan. Japan still has the most ridiculously expensive but visually appealing fruit. And I still love it.